This report discusses what containers are and how they differ from virtual machines (VMs). The threats and vulnerabilities to containers are summarised based on research findings. Major threat categories of containers are discussed and high level advice for mitigations and countermeasures is offered.

Photo by Ian Taylor on Unsplash

Photo by Ian Taylor on Unsplash

Introduction

This report shall discuss why containers have become popular in recent years and differ from virtual machines (VMs). It will explain the critical components of containers and the container ecosystem and discuss the history of Docker and how Kubernetes came to dominate the container market. In addition, the report summarises research into container threats and vulnerabilities and offers mitigations and countermeasures for these threats, as well as strategic advice to enterprises for improving container security.

Why Containers?

In the early days of the dot-com boom of the 1990s, internet applications and services ran directly on physical hardware with an operating system. This was commonly known as a “bare-metal” install. Applications and services had significant costs and overheads, especially in n-tier application architecture, which dictated that separate service components such as the web, database, and application services should run on separate servers. The introduction of server virtualisation technology allowed a single physical server (known as a host) to run multiple virtual servers (known as guests), each on its own VM. This cost saving and flexibility over bare-metal began the transition of internet services to cloud computing. As the demand for computing grew, so did the number of VMs needed by enterprises. Containers have become popular as innovations in application design have favoured microservices architecture, the adoption of DevOps methodologies like Continuous Delivery (CD)/Continuous Integration (CI) and the growth of public cloud. The demand for applications to be created and destroyed quickly and efficiently has seen containers grow to 15% of all enterprise applications in 2020, with predictions the market will be worth $950 million by 2024 (Sharwood, 2020). Containers are popular with application developers because:

- Containers are lightweight compared to VMs. They take up less disk space, start and stop much faster, and use less memory.

- Containerised applications are portable compared to VMs because they include all required dependencies such as libraries, binaries and runtime environments.

- Containers are scalable, and it is easy to increase or decrease the number of containers to meet demands.

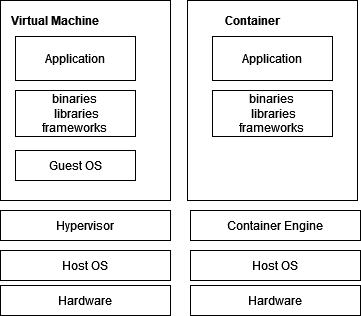

Compared to VMs, containers are tightly coupled with the host operating system. Individual containers do not run their own copy of an operating system. This makes containers faster and lightweight but comes at the cost of compatibility as binary and library dependencies are tied to the host operating system kernel (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1 - The virtual machine stack vs. the container stack

Explaining the Container Ecosystem

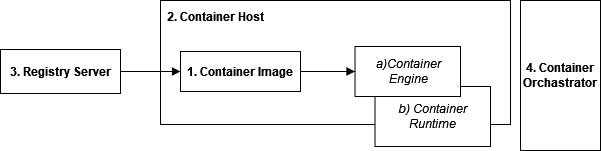

Containers consist of four main components (see Figure 2) being (McCarty, 2021):

1. The Container Image

The file that makes up the file system of a container. The image includes libraries and binaries needed for a running application. It follows a format defined by the Open Container Initiative (OCI) and is stored on the Registry Server.

2. The Container Host

This is the computer system on top of which the container executes the Container Image. The Container Host contains the following elements:

a) The Container Engine

The Command Line Interface (CLI) accepts user requests to pull images from the registry server and start and stop images on the Container Host.

b) The Container Runtime

The lower-level component of the Container Engine that actually runs the container. Early versions of Docker Engine used LXC as a runtime. Later, Docker built its own version, which was open-sourced and called Runc. Kubernetes has deprecated the use of Runc and now uses its own container runtime called CRI-O.

3. The Registry Server

The file repository for container images which are created and pushed to the server and pulled from the server to run on the container host

4. The Container Orchestrator

The orchestrator is used for wiring containers together so that they may be deployed as a unit. It can create pipelines with these units and deploys them across different container hosts. It can also dynamically schedules container workloads in a cluster of computers, such as scale-up/scale down.

Figure 2 - The Components of Containers

There are so many vendors, platform providers, and software name components in the container ecosystem that it can be confusing. The reason for this may have to do with what Fulton (2020) describes as “the shortest technology battle in computing history”. In 2013 technology startup Docker, Inc. began the container revolution and created software products that serviced the four container components. They were:

- Docker Compose for creating container images;

- Docker Engine/Daemon for the container host;

- DockerHub as a public registry server for container images; and

- Docker Swarm as a container orchestrator.

Although Docker may be synonymous with containers and many research papers such as Sultan et al. (2019) cite Docker as the “predominant container technology”, and Wong et al. (2021) states that Docker is “the most widely employed container runtime” with 79% market share, according to Fulton (2020) Docker has lost the container war to Kubernetes.

Google created Kubernetes in 2014 to manage and orchestrate containers with the Docker runtime as an alternative to Docker Swarm. In 2015 Google open-sourced Kubernetes and created the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) in what Fulton describes as “suspect timing”. In 2020, Kubernetes deprecated the Docker Engine in favour of its engine called CRI-O (Kubernetes, 2020). Kubernetes has come to dominate the market as the platform for running production container workloads. All major public cloud providers offer Kubernetes as Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS). Openshift (by Redhat) is even sold as an end-to-end container solution for the enterprise that manages Kubernetes clusters for private and public cloud landing zones (Herness, 2021). Docker Inc. failed to capitalise on the container market but continues to exist as a developer tools company. Developers still use Docker Compose for image creation and DockerHub as a registry server, and Docker Engine is the container host developers use to run containers locally for development, but Docker products have failed to gain market share in running container workloads for production environments.

Publicised security incidents with Containers

There have been several highly publicised security incidents with containers have led to a perception that containers are not as secure as VMs. In 2017 a threat actor created several DockerHub images which contained a cryptocurrency miner for the Monero digital coin. The images were downloaded over 5 million times and mined 545 coins (worth approx $90,000 at the time) before the images were taken down (Goodin, 2018). In 2019 a hacking group was discovered mass-scanning more than 59,000 IP networks on the internet, looking for exposed Docker Swarm API endpoints, sending commands to start malicious containers to mine cryptocurrency (Beedham, 2019). Also, in 2019, DockerHub had a security breach where usernames, hashed passwords, Github, Bitbucket tokens were stolen. This breach meant threat actors could compromise containers owned or published by users on DockerHub (Cimpanu, 2019). In 2020 a cybersecurity company scanned 4 million container images on DockerHub and found that 51% had vulnerabilities and 0.16% had malicious software Wong et al. (2021).

New technology, same old threats

Many of the threats and vulnerabilities of container hosted applications are the same as running applications in more traditional ways, such as bare-metal or VMs. Application-level security risks described by projects such as the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) still exist on containers, as do vulnerabilities in the (shared) libraries underlying applications. Containers are designed to be immutable, meaning that if applications or libraries require patching or updating, then the container needs to be rebuilt as a new image and the image redeployed and restarted on the container host. Operating system-level patching of vulnerabilities still needs to occur, but this is outside of the container (see Figure 1). A host operating system running multiple containers only needs to be patched once.

Threat Modeling for Containers

A recent research paper by Wong et al. (2021) performed the STRIDE threat model against the three main components of Docker containers, i.e. the registry server, the container host and the container image. The analysis included traditional threats from application vulnerabilities and the container host operating system. The results are summarised in Table 1 .

| Threat Categories | Threats |

|---|---|

| Spoofing | 4 |

| Tampering | 4 |

| Repudiation | 2 |

| Information Disclosure | 3 |

| Denial of Service | 2 |

| Elevation of Privilege | 4 |

Table 1 - Summary of STRIDE threats for containers found in Wong et al. (2021)

Researchers Sultan et al. (2019) performed a literate review of container security and found three major threat categories for containers: container image security, container-to-container security, and host-to-container security. This report will use these threats categories for its discussion.

1. Container Image Security

Threats and Vulnerabilities

Container images pose the most significant threat and attack surface. The idea behind a registry server such as DockerHub was that developers share, reuse and build on containers built by others. This has meant that public registry servers have become a significant supply-chain threat. Enterprises that rely on containers built by third parties could allow malicious code or unpatched vulnerabilities to run in their environments. Reliable third parties are also subject to compromise, leading to malicious code running in a container. Container images can be compromised in transit if there is no image verification or the publisher does not sign container images. Image compromise can be achieved through a man-in-the-middle (MIM) attack, DNS poisoning, or even typo swatting on the image names (Morag, 2021).

Mitigations and Countermeasures

The common recommendation for mitigating the threat of image containers is to deploy vulnerability and malware scanning tools to CD/CI pipelines that build container images. Even so, this is not a complete solution. Research by Javed (2021) tested container scanning tools and found the detection-hit-ratio to be 65%. This means enterprises need to take great care in building and maintaining images using good security practices and not simply rely on scanning tools as an afterthought. Cloud providers offer private server registries; meaning organisations can source images from trusted sources, add their own components and build images in a private registry. Containers should be deployed into test environments and undergo security auditing before being approved for deployment into production.

2. Container-to-Host isolation

Threats and Vulnerabilities

One of the disadvantages of containers over VMs is that the container and the host OSes are more tightly coupled. This means that if privilege escalation is achieved inside the container, it is much easier to take control of the host (which could be running hundreds of containers). In VMs this would not be possible as each machine runs its own kernel, making it isolated to the underlying host operating system. This type of exploit is known as container escape, and there are published Common Vulnerability Exposures (CVEs) using these exploits; CVE-2017-5123 and CVE-2016-5195 Sultan et al. (2019). There are also threats created to the underlying host due to shared storage. Containers are considered immutable, which means that persistent storage that needs to maintain state (such as database files, or log files) needs to be maintained in storage on the underlying host or network storage. This creates additional challenges for data security and for SIEM/SOAR Wong et al. (2021).

Mitigations and Countermeasures

The most common recommendation for improving container-to-host isolation is to use operating system level tools which come with Linux, such as SE Linux and AppArmor. Another alternative is to change the container runtime. The default runtimes for Docker and Kubernetes are RunC and CRI-O, respectively. They allow unrestricted kernel calls to the host OS. More secure alternatives add an extra layer of security to restrict what kernel calls the container can make to the host OS. Research by Viktorsson et al. (2020), tested popular alternative runtimes and found that this countermeasure security makes containers run 40 to 60% slower. Enterprises may also want to use a hybrid model that combines the use of VMs and containers to maintain host-to-guest isolation. Enterprise tools such as OpenShift are designed to use this hybrid model.

3. Container-to-Container isolation

Threats and Vulnerabilities

By default, containers on Docker use private-host networking allowing open communication between containers on the same host. With Kubernetes pods (a pod is a collection of containerised applications and volumes), there is open network communication between containers no matter what host they run on. This means that traditional attack methods can be used to compromise one container, such as remote code execution (RCE), by finding and exploiting open network services, ARP spoofing, or MAC flooding. By default, containers do not have resource limits, thus risking DoS attacks. Consuming resources (CPU/memory/disk) on one container can lead to the exhaustion of the resource on all containers. Sultan et al. (2019)

Mitigations and Countermeasures

Native OS tools such as Namespaces are recommended for grouping containers together to improve container-to-container isolation and CGroups can be used to limit CPU/memory resources. Kubernetes can also be configured to set resource limits on containers. Using a VM and container hybrid model can also mitigate container-to-container security risk.

Conclusion

The adoption of containers by enterprises for running applications will continue to grow. Many of the old threats of running internet applications still exist, albeit sometimes with some new twists, such as the supply-chain risk posed by container image security. The support for security tools to operate within container environments should improve as the container market matures. Enterprises need to ensure they have a container security strategy that will adapt existing security practices and integrate them with container technologies.

References

Altvater, A. (2019, May 1). What is N-Tier Architecture? How It Works, Examples, Tutorials, and More. Stackify. https://stackify.com/n-tier-architecture/

Beedham, M. (2019, November 28). Hackers mass-scan for Docker vulnerability to mine Monero cryptocurrency. The Next Web. https://thenextweb.com/news/hackers-mass-scan-for-docker-vulnerability-to-mine-monero-cryptocurrency

Cimpanu, C. (2019, April 27). Docker Hub hack exposed data of 190,000 users. ZDNet. https://www.zdnet.com/article/docker-hub-hack-exposed-data-of-190000-users/

Fulton, S., III. (2020, January 28). After Kubernetes’ Victory, Its Former Rivals Change Tack. Data Center Knowledge. Retrieved 12 January 2022, from https://www.datacenterknowledge.com/business/after-kubernetes-victory-its-former-rivals-change-tack

Goodin, D. (2018, June 14). Backdoored images downloaded 5 million times finally removed from Docker Hub. Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2018/06/backdoored-images-downloaded-5-million-times-finally-removed-from-docker-hub/

Herness, E. (2021, December 24). Hybrid Cloud Decisions: When to Target Public and Private? Medium. Retrieved 16 January 2022, from https://medium.com/hybrid-cloud-engineering/hybrid-cloud-decisions-when-to-target-public-and-private-f3a6c3c0ed4a

Javed, O. (2021, January 11). Understanding the Quality of Container Security Vulnerability. arXiv.Org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.03844

Kubernetes. (2020, December 22). Don’t Panic: Kubernetes and Docker. Retrieved 12 January 2022, from https://kubernetes.io/blog/2020/12/02/dont-panic-kubernetes-and-docker/

McCarty, S. (2021, December 6). A Practical Introduction to Container Terminology. Red Hat Developer. Retrieved 15 January 2022, from https://developers.redhat.com/blog/2018/02/22/container-terminology-practical-introduction

Morag, A. (2021, August 12). Threat Alert: Supply Chain Attacks Using Container Images. Aqua Blog. Retrieved 12 January 2022, from https://blog.aquasec.com/supply-chain-threats-using-container-images

Sharwood, S. (2020, June 25). Containers to capture 15% of all enterprise apps across 75% of business by 2024. The Register. Retrieved 10 January 2022, from https://www.theregister.com/2020/06/25/container_forecast_gartner/

Sultan, S., Ahmad, I., & Dimitriou, T. (2019). Container Security: Issues, Challenges, and the Road Ahead. IEEE Access, 7, 52976–52996. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2019.2911732

Viktorsson, W., Klein, C., & Tordsson, J. (2020). Security-Performance Trade-offs of Kubernetes Container Runtimes. 2020 28th International Symposium on Modeling, Analysis, and Simulation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems (MASCOTS). https://doi.org/10.1109/mascots50786.2020.9285946

Wong, A. Y., Chekole, E. G., Ochoa, M., & Zhou, J. (2021, November). Threat Modeling and Security Analysis of Containers: A Survey. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.11475