This post breaks down what the term living-off-the-land (LOTL) actually means in cybersecurity for defenders. Malware-free, file-less malware, LOTL, they are all terms used to describe threats, sometimes interchangeably, but do the mean the same thing? The lines between legitimate user operations and malicious activities have become blurred.

Photo by James Baltz on Unsplash

Photo by James Baltz on Unsplash

The new reality

Picture this: You’re reviewing a device timeline in the Microsoft 365 Defender portal after a suspected breach. All the suspicious entries you see involve native Windows binaries: powershell.exe, cmd.exe, rundll32.exe. There’s no obvious giveaway: no Mimikatz dumping credentials, no telltale ransomware payload pulled down by a browser. You know something isn’t right. But Defender hasn’t raised any alerts? It’s as if you’re chasing ghosts. This is the new reality for security teams.

This type of stealthy intrusion has become the new normal. State-sponsored APTs and even low-rent ransomware operators weaponise legitimate system tools rather than deploy malicious executables. These types of attacks have varying names: malware-free, file-less malware or Living-off-the-Land (LOTL) attacks. In this post, I’ll explain what the these terms mean, I’ll take a look at two community projects that document LOTL TPPs (tactics, threats and procedures) and I’ll attempt to explain the varying definitions of LOTL.

When is malware not malware?

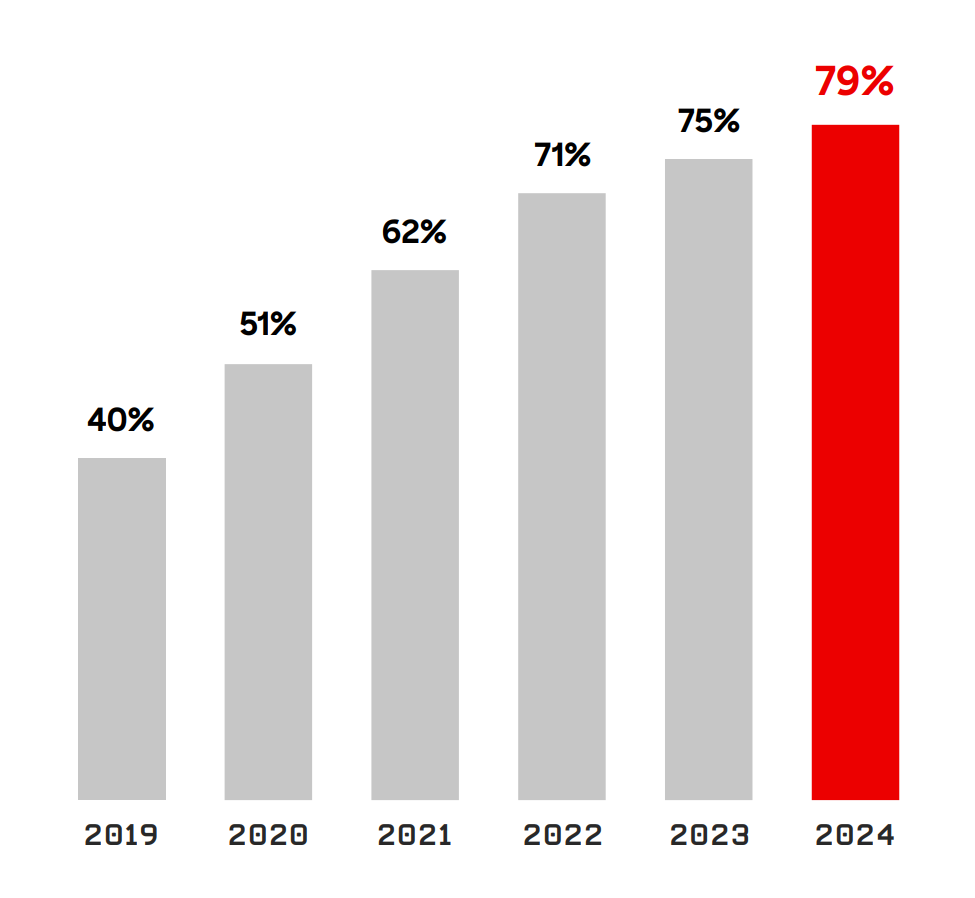

According to CrowdStrike’s 2025 Global Threat Report, 79% of detections in 2024 were malware-free. Figure 1 below highlights the increasing trend of malware-free detections. CrowdStrike defines malware-free attacks as intrusions where no malicious binaries are written to disk. Instead, adversaries use system tools like PowerShell or Remote Desktop, operating in-memory or with hands-on-keyboard techniques.

Figure 1: Rise of Malware-Free attacks in CrowdStrike’s Annual Threat Reports

Source: CrowdStrike Global Threat Reports

Malware-Free ≠ Attack-Free

Malware-free does not mean attack-free. It means attacks don’t rely on traditional malicious files. File based detection has become fast and effective with websites like Virustotal becoming the universal repository for malware identification. By operating entirely in-memory or using built-in operating system tools, attackers can bypass signature-based anti-viruses and avoid detection.

LOTL: An Origin Story

Traditionally, the phrase “living off the land” describes the practice of subsisting on natural resources through farming and hunting. In cybersecurity, this same concept is applied to threat actors exploiting installed binaries, scripts, and native OS tools on target systems to carry out malicious objectives.

The phrase and the acronym LOTL were first popularised at the hacker conference DerbyCon in 2013, along with related terms like LOLBins and LOLBAS (Living-off-the-Land Binaries and Scripts). Shortly after DerbyCon, a collective effort called the LOLBAS Project launched on GitHub. Its goal was to:

- Document every Windows binary and script with hidden or unexpected features that attackers might exploit; and

- Map each of these LOLBins to known tactics within the MITRE ATT&CK framework so defenders can see which stage of an attack a particular binary might be used in.

Unlike CrowdStrike’s broad, all-encompassing definition of malware-free attacks, the LOLBAS Project applies a much narrower set of criteria for inclusion. To for a file to be listed on the project website, it must:

- Be Microsoft-signed (i.e., trusted by the operating system);

- Possess unexpected functionality that threat actors can exploit, and;

- Map to a legitimate tactic or technique in MITRE ATT&CK.

Hey Windows, get the F**ck off my lawn!

A few years after LOLBAS project took off, a similar project started for Unix-like systems called GTFOBins (Get the F** Out Binaries*). It was created in 2018 by security researchers inspired by the Windows based LOLBAS project. GTFOBins began cataloguing legitimate binaries that could be abused for privilege escalation, command execution, and data exfiltration on Unix systems. The project has a wider definition for what they include as a LOTL binary. If the tool is typical on Unix machine and can help an attacker perform a task to bypass security restrictions or some other abuse by an attacker, no matter how obvious the functionality is, then it’s in scope for the project.

Here’s a table summarising the differences between the projects:

LOLBAS vs GTFOBins: A Quick Comparison

| Feature | LOLBAS (Windows) | GTFOBins (POSIX based) |

|---|---|---|

| Platform | Windows | Unix-like (Linux, macOS, etc.) |

| Signature requirement | Must be Microsoft-signed | No signing requirement |

| Focus | Exploiting unexpected or non-obvious functionality | Exploiting any useful functionality |

| Inclusion criteria | Strict (signed, exploitable, maps to MITRE ATT&CK tactic) | Broad (any native binary that can assist in an attack) |

| Examples | rundll32.exe, mshta.exe, regsvr32.exe |

bash, awk, scp, find, perl |

| Primary use case | Defender awareness of obscure abuses in trusted binaries | Attacker-friendly reference for post-exploitation tactics |

| Project URL | LOLBAS | GTFOBins |

LOTL: Blurred Lines in Practice

While the LOLBAS and GTFOBins projects define clear inclusion criteria, the real-world application of LOTL concepts often blurs these lines. Many tools used by traditional file based malware also use built-in system utilities with expected functionality, but used maliciously. Take vssadmin.exe, for example, it’s commonly used by ransomware to delete Volume Shadow Copy (VSS) backups before encrypting files. Although this is expected behaviour, most analysts would still call this a LOTL technique.

This practical ambiguity is reflected in how security researchers, cyber threat intelligence firms, and national cybersecurity agencies classify such activity. Rather than attempting to categorise an attack as file-less malware, a LOLBAS binary or a LOLBin, these groups often use the term “living off the land” as a catch-all phrase. A prime example of this was the Five Eyes security intelligence agencies joint report in 2023 on state-sponsored threat actor Volt Typhoon.

2023 Volt Typhoon report

The Volt Typhoon campaign, attributed to a Chinese state-sponsored actor targeted US critical infrastructure exemplifies the LOTL threat.According to Microsoft’s analysis, Volt Typhoon used a range of native Windows utilities like PowerShell, WMIC, netsh, and ntdsutil to perform tasks like system discovery, credential access, and data exfiltration. The most frightening part of the report was that many of the IOCs (Indicators of Compromise) were ambiguous because the commands are commonly used in routine IT operations. For example attackers used netsh to create and later delete port proxies on compromised systems. While netsh is a legitimate tool, its use in this context can be indicative of malicious activity.

Conclusion

The LOTL methods of using the system’s own tools against itself is now the default mode for cyberattacks. With file-based malware detection being so effective, it’s no surprise that threat actors have shifted to LOTL techniques, which are harder to detect and defend against. Traditional antivirus solutions that rely on file signatures have become obsolete, with nearly 80% of attacks now classified as “malware-free.” So, how do you defend against LOTL? In an upcoming post, I’ll explore the countermeasures enterprises are adopting and examine promising research aimed at helping defenders get a handle on LOTL threats.